There is nothing to do except pace the hallway and swallow pills in a psych hospital. So I decided to speak with my peers.

Inside the Community

“So, how did you get here?” I asked an unsuspecting peer on the ward. He was around my age and appeared somewhat approachable, speaking in words I found sensible, at first.

“Police brought me to CPAP… ” He said with empty conviction. It was as if it had happened to him, but he didn’t know anymore about the story.

The most insightful person will tell you ‘why,’ and ‘how,’ they went inpatient.

CPAP is an emergency room, but configured for psychiatric emergencies. So, when I asked why he was admitted, he told me not why, but how. He left out the most critical details leading to his hospitalization, providing little information about what was going on with him.

Peers on the unit carry with them insight (or lack thereof) and stories that can pass the time on days when you need to escape, if only mentally, the confines of the unit. After so many hospitalizations, I have experienced the benefits and drawbacks of socializing with others in the hospital.

Today, specialized units and other specialized care settings target specific disorders and cater to a niche cross-section of the mental health community. Psychiatric units, like local restaurants, now cater to a particular client base, or diagnosis, when accepting new admissions.

Socializing shaped my understanding of my own mental status on the unit. The better I understood others’ stories, the more I understood about how the hospital staff was trying to help those patients.

Ah-ha! Moments

More interesting than how the system works, however, are the stories of how my peers discovered themselves within an inpatient setting. People’s versions of the precipitating events which led to their hospitalization is always fascinating. The most talked-about stuff on the ward—bar none—paints a picture of a peer with more humanity.

“Look!” A patient gestured to her wrist, where she carved “HELP” into her skin with scabs and stitches. Her skin was still red and irritated looking.

Understanding how minor problems become bigger is interesting on a clinical level. For her, help would mean feeling less pain. The hospital, for her, would ideally help her find ways of soothing the pain and guide her toward finding more comfort in her thoughts.

Why and How

The ward, or unit, sometimes feels like a place of healing and sometimes feels like jail. Depending on why and how someone gets there, their story will foreshadow their course of treatment. I like to think of it as socialization. After all, I’m talking with others on the unit, or getting to know the more significant peer community.

Similarly, there is an invisible energy trail as patients pass through vitals and other triage areas on the unit toward their room and the patient regions. When a new patient sits down with everyone in the patient peer community or for their first meal, there’s always a moment of anticipation, excitement, and total shock.

New Admissions (Fresh Meat)

New admissions were “fresh meat.” These patients were always at their peak, the most disordered, and at a severe point in their illness. These folks seemed to always leave a wake as a giant ship does to the surrounding water.

Everyone usually gasps when the unit door opens and walks to a new admission, followed by an unmistakable pause. “Who is this?! What’s their diagnosis?” We whisper to one another.

New admissions to the unit are usually not healthy enough to engage in meaningful communication. In terms of approachability, many are still agitated. Making connections with other peers is a precarious venture in the hospital. It is almost impossible to know how socializing will pan out or benefit your situation.

Stories from newly admitted peers can and probably will be highly vivid, sometimes dark, and usually bizarre. “I am the lord’s anointed one, ready to usher in the age of judgment,” I distinctly remember hearing from a new admission.

At the same time, most people talk about their potential and future discharge. You may be lucky enough to catch someone in their low-level manic reflective mood talking about their feelings on how they ultimately needed the hospital. Reflection is followed by a litany of regrettable situations culminating in each patient’s “eye-opening” admission. “That’s how I got here…” you would hear, repeatedly, with more or less insight each time.

“Den of thieves!” shouted a patient. I turned my head to glance at him then looked back ahead. Wow, what a special place this is.

Dirt and flowers were always falling out of her pockets on the floor. Even more strange, staff members constantly reminded Carol to stop taking ground from the flowerpots in her room.

Carol, or ‘Carol Flowers’, as she later referred to herself in writing, reminds me of the strange subtext that follows patients and new admissions.

First Admission

Given all the covert technical aspects surrounding patient engagement, it isn’t too hard to see that making friends on the unit can be highly complicated. My first adult admission was at age 20, at the peak of my mental development, a few months before I turned twenty-one. I was supposed to be at my graduation ceremony from Binghamton University.

Instead of attending graduation, moving up meant admission to the local hospital in Binghamton. If my situation wasn’t sad enough, I was transferred from the community hospital to the state after “failing out” at the lower level of care.

As a college student, you could understand why I wasn’t familiar with this tiered system. I was puzzled as to why the same engagement skills I had just learned at one level of care weren’t working when I arrived at the state hospital. At the state level of care, patients seemed to be more reactive, requiring more careful interaction.

I still remember attempting to make conversation with a few people without any success before giving up. Most patients produced word salad or garbled language. “Banana, I’m tired”. Mumbled a peer, perplexing me ad nauseum. Unless a staff member was present, their speech was indecipherable. Most of them eventually fell off my radar until their speech cleared up. Or until I could make some sense of what they were trying to say.

Ground Floor of Dysfunction

People are so disordered that they cannot maintain a conversation without spinning out in tangents and non-sequiturs without end. “God, damn!” I thought, listening to this patient speak. Almost every other word was out of sequence or misplaced, except for one sentence: “I’ve been up and down this hill,” remarking on her long relationship and rich history of hospitalizations on the hill, the local vernacular for the name of the hospital’s campus.

I wasn’t the only sick person who was hard to understand regarding essential engagement and communication. Depending on their diagnosis, other people encounter issues when holding a conversation. It was even more challenging to get someone’s entire picture for more extended, rawer, and more reflective discussions.

Life in the unit is full of dull moments. Sometimes, with all the silence, interrupted only by treatment meetings and everyday team operations, it was hard to keep your head together. Talking with my unit mates offered a welcome break from the atmosphere.

Stabilization

I have heard stories of all kinds, painted in both broad and sophisticated strokes depending on the mood, verbal acuity, or differing levels of self-disclosure.

One patient, Lady R. I got along with Lady R. well and spoke with her regularly. In Lady’s case, it seemed as if she was recovering. So, I invested my energy in speaking and connecting with her. I wanted to know what she was doing to experience some relief from her symptoms, whatever they were. I wanted to learn more.

One day, it seemed as if a switch had flipped. Suddenly, Lady was talking to herself again and responding to internal stimuli. One day, I noticed she was talking with hospital staff and pointing toward me. I was sitting on the couch in the day room at the time. The team approached me and asked me what I was doing now.

“Max, one of the nurses wants to speak with you.” One of the technicians advised me one day that speaking with her seemed not only to be tricky, but troubling. I knew it! The other patient was complaining to the staff about me. She’d told the team that I was threatening her.

That was what the nurse told me later. I had to vouch for my behavior to the nursing staff and luckily they believed me. After about a week, the team transferred Lady to long term care.

In this case, I was entangled in Lady’s delusional system, and she reported it to staff. After looking into it, the team must have decided she was de-compensating and needed more help and stabilization than the admissions unit offered here.

Yearbook

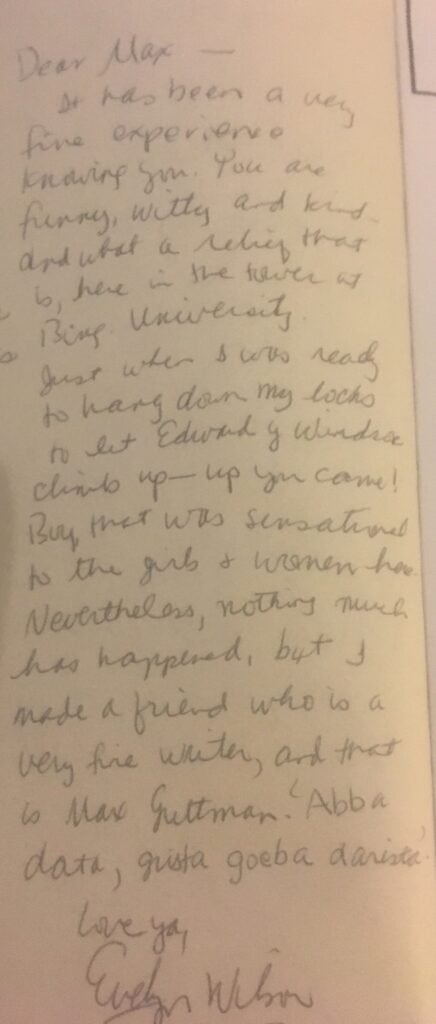

Upon discharge, my family surprised me with a copy of my college yearbook they ordered before being hospitalized. “It didn’t seem right to give it you earlier…” My parents said as they handed the school yearbook from Binghamton University..

I have several comments and signatures, including Carol Flowers and others from people I socialized with in the psych hospital.

In the yearbook’s pages are inscriptions of their good wishes for me after discharging and moving on.

It was a space for their hope for a better future for me.

The inspiration, challenges, stories, and suggestions we get from socializing during difficult times (and good times) will live on for another day. I hope it will persist far beyond the confines of the hospital. Let it aid you in reaching the upper limits of healing.

J. Peters

Book Author.